Edward Degas story starts out as one of those lovely “Dad wanted me to go to law school but I said ‘Nay Father. Art is my life!'” type affairs.

Edward Degas story starts out as one of those lovely “Dad wanted me to go to law school but I said ‘Nay Father. Art is my life!'” type affairs.

Son of Banker Augustin De Gas, Degas first act of defiance was to change his last name to something slightly less pretentious sounding. After this, it was to pursue art. This was all very early in his life, and by the time he was 18 he’d turned his bedroom into a studio for his paintings. It was after this, that Dad told him to go to law school, which like a dutiful son, he did. He enrolled at the Faculty of Law of the University of Paris in 1853, but didn’t really put much effort into his studies. Two years later, in 1855 Degas met fellow French artist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. Now, who of my few loyal followers recognises that name? We spoke a little bit about Ingres a few weeks ago in the post about Odalisque art. Degas was very taken with Ingres, who had told him to “Draw lines, young man, many lines”. Inspired, Degas went to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts later that year (Ecole des Beaux-Arts is still a very influential art school in Paris). Here, Degas studied with Louis Lamothe (1822 – 1869). After this, in 1856, he moved to Italy and started copying some of the great works by people such as Michelangelo and Raphael, etc.

Degas continued to copy pictures and began to make a healthy living as a copyist whilst working on original works. He began working on studies of horses. His painting Scene from the Steeplechase: the Fallen Jockey marked a departure from the more traditional history paintings, to more contemporary subject matters. This change was partly inspired by another French buddy of Degas called Édouard Manet (1832 – 1883). This was a very important moment in Degas artistic career when he began to draw scenes from real life. These included many scenes of horse tracks and, of course, of ballerinas. This may seem pretty standard now, but depicting scenes from everyday life was quite rare at the time.

This change was partly inspired by another French buddy of Degas called Édouard Manet (1832 – 1883). This was a very important moment in Degas artistic career when he began to draw scenes from real life. These included many scenes of horse tracks and, of course, of ballerinas. This may seem pretty standard now, but depicting scenes from everyday life was quite rare at the time.

Degas is sometimes called the ‘Painter of dancing girls’. There are a few reasons for his obsession. Some, believe it to be voyeuristic, but others have disputed this claim. It’s a fact that dancers and models at the time often worked as prostitutes on the side, due to poor wages. It is almost certain that Degas did not partake of any of this, but there are plenty of nude pictures that would have been modeled by these girls. There are also stories of him making his models stand in painful positions for hours on end. Perhaps there was some sort of cruel satisfaction to be had this way. There’s also the possibility that this was purposeful, and Degas was making a point about the physical harm that ballerinas do themselves in the pursuit to master their discipline. All Degas wrote himself on the subject was;

It has never occurred to them that my chief interest in dancers lies in rendering movement and painting pretty clothes.

Degas was a huge fan of the opera and ballet and Paul Trachtman writes; ‘At the ballet Degas found a world that excited both his taste for classical beauty and his eye for modern realism.’ He used the ballet as a way to create new forms of painting that could describe fluidity and movement. The ballerinas are probably Degas most famous and well received works.

In 1870 Degas joined the National Guard with the start of the Franco-Prussian War. For obvious reasons, Degas didn’t do too much painting during this time, and what’s worse, he developed a defect in his eyesight, which continued to bug him for the rest of his life.

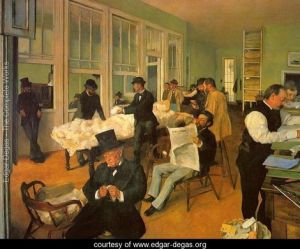

The war ended in 1872 and Degas stayed in Louisiana with some family members for a year. During this time he painted a number of works depicting family members. This painting below (painted during this time) was the only one of his works to be bought by a museum during his life.

In 1874 (by which time Degas was back in Paris) his father died. Then it came to light that Degas brother had been a bit careless with his monies. To keep the family afloat (and respectable) financially, Degas sold his house and art collection. For the first time in his life, Degas was actually dependant on his art sales to live. He stopped doing profitless exhibitions, and joined a group of artists who were intent on making a society for independent exhibitions. The exhibitions these guys were putting on quickly became known as ‘Impressionist Exhibitions’. Even though Degas hated the title he took a lead role in the Imperialists exhibitions.

As I said, Degas hated the title, and the reputation the Imperialists had. He was pretty public about this opinion which didn’t really do him any favours in the group. Some people say that he was actually as anti-Impressionist as some of the critics were. His style and method of work were also not very Impressionist. He kept to his darker paint pallet rather than adopting the bright colours of the Impressionists and he always worked indoors. In fact, he often made fun of the Impressionists for their tendency to paint outdoors.

He also insisted on including some more traditional painters in the exhibitions. All of this helped to pull the group apart and they disbanded in 1886. By this time though, Degas was making a reasonable living from his art.

Unfortunately Degas eyesight remained problematic and got much worse as he grew old. As a way to combat this, Degas started to sculpt. He started making wax figures, possibly as a way to work on something that he could mould and feel now that his vision was failing. The most famous sculpture of Degas isThe Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer. It’s a wax sculpture that stands at 39 inches and is adorned in real clothes – a tutu and ribbon for the hair (which is a wig). The figure is based on a real dancer called Marie van Goethem, who was sometimes referred to as ‘little rat’. The reception of her sculpture isn’t much better and it was often referred to as being ugly. This ugliness at the time was also linked to the idea of loose morels, and questions of Degas sexuality and voyeuristic leanings are again brought into question.

It’s a wax sculpture that stands at 39 inches and is adorned in real clothes – a tutu and ribbon for the hair (which is a wig). The figure is based on a real dancer called Marie van Goethem, who was sometimes referred to as ‘little rat’. The reception of her sculpture isn’t much better and it was often referred to as being ugly. This ugliness at the time was also linked to the idea of loose morels, and questions of Degas sexuality and voyeuristic leanings are again brought into question.

One thing I’d like to point out which I think is wonderful, is that when Degas made the original, he created a skeleton out of paintbrushes! Isn’t that great? I love the idea that she was completely made up of his own art tools. You can still see this sculpture nowadays, but mostly only in brass reproductions.

And here’s where it all gets a little depressing…

As he grew older, Degas secluded himself from many people because apparently he believed that artists can’t have personal lives. After this, in the early 1890’s it became apparent that Degas had certain antisemitic qualities. This obviously caused all his Jewish friends to break contact with him, and Degas became very lonely. He stopped painting in 1912 and was thereafter forced to leave his long term home due to demolition. He moved to quarters on the boulevard de Clichy. He didn’t marry, his eyesight got worse and he died, half blind, wandering the streets of Paris in 1917.

All of these artists have such morbid ends…I’m hoping to find some artists who didn’t die alone or disease ridden soon, or else I might start to question my own life decisions.

To check out Degas’ complete works check out this great site.

Next up: Poker playing Dogs.

Great blog – loads of things I never knew here! In fact, the poor suffering artist is a bit of a myth. Monet was in the money in a big way by the end of his life (remember those water lilies were in his garden!) and Rodin was flush with cash too and lived in luxury. I think the legend springs from Van Gogh and his obvious poverty, but many of his contemporaries did very nicely out of their work.

Thank you!

Yes, I think you’re right, also the whole impoverished artist thing has almost become a fashion statement in some circles.