Being involved with the first ever stage adaptation of a Studio Ghibli film, it will come as no surprise to anyone that I’m surrounded by other Ghibli enthusiasts and general anime fans. Of course, when surrounded by these sort of people and these subjects, one will undoubtedly find their interest in such things re-ignited with more fire than before. This is certainly how I am feeling at the moment and because of this I have been watching a number of anime titles I have up to this point never seen before.

Being involved with the first ever stage adaptation of a Studio Ghibli film, it will come as no surprise to anyone that I’m surrounded by other Ghibli enthusiasts and general anime fans. Of course, when surrounded by these sort of people and these subjects, one will undoubtedly find their interest in such things re-ignited with more fire than before. This is certainly how I am feeling at the moment and because of this I have been watching a number of anime titles I have up to this point never seen before.

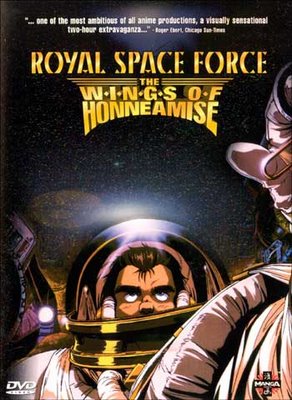

Last night, I watched a fantastic little film called Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honneamise.

Wings of Honneamise was released in 1987 and is the first and only full length feature film produced by animation studio Gainax. The film takes place in an alternate version of Earth in which an industrial revolution is flourishing despite the impending war between two nations (Honneamise and ‘The Republic’). At this time, the Space force is working (much to the amusement of the ‘real’ military) towards putting the first man in space. That man is Shirotsugh Lhadatt, who only joined the space program because he didn’t qualify to join the more reputable air force. Lhadatt is a bit of a slacker, only continuing his work with the space program as a way to ensure he can continue to live comfortably compared to the many homeless and jobless of Honneamise.

Whilst wandering the streets one night he meets Riquinni Nonderaiko, a kind hearted religious girl who is preaching against the many injustices and sins of the world. The two become friends and Riquinni’s enthusiasm about what the space program symbolises rekindles Lhadatt’s pride in the program. This is why he volunteers to take the role of first astronaut, despite the obvious danger to himself.

And this is pretty much the basis of the film. From here on we learn about the characters, we see the effect the space program has on both the people and the governing body of Honneamise, we watch the conflict between the two nations build, using the space program as a catalyst to wage their inevitable war, and we see the growth of our main characters.

Wings of Honneamise is generally considered one of the finest examples of Japanese adult animation. However, most reviews are often worded something like this:

‘One scene short of a masterpiece.’

‘One of the best animes I’ve ever seen, despite ‘that’ scene.’

‘A beautiful film ruined by one ugly scene.’

Many, many people agree that there is a single scene in the film, often referred to as ‘that scene’, which soils the overall experience the film offers. If you have seen the film, you will instantly know which scene I’m referring to. If you haven’t, then you should know that I’m about to start giving away spoilers for the film, so if you intend to watch it, you might not want to read on.

The scene in question comes about two thirds into the film, when Lhadatt attempts to rape Riquinni in her home. The scene is very coldly realised and unrelenting in its portrayal of the act. Lhadatt attacks Riquinni as she is undressing, pinning her to the floor before he realises what it is he’s doing and stops himself. At this point Riquinni gives him a well deserved braining with a candlestick, knocking him unconscious. The next morning, as Riquinni is leaving home, Lhadatt runs after her to apologise but instead she insists that she be the one to apologise for hitting him. ‘You’ve done nothing wrong,’ she says, ‘You’re a wonderful person and I shouldn’t have hit you. Please forgive me or I shall never forgive myself.’ Well, that all sounds pretty awful and misogynistic now doesn’t it? But y’know…I’m not so sure.

Now, before I go any further, allow me to explain myself. I despise the way rape is used in media nowadays. It seems to me that whenever a story requires a female character to be hurt, traumatised or damaged in any way, rape is the first port of call. Whenever a man has to be shown as being evil, he’ll rape, or threaten to rape someone. Websites such as Women in Refrigerators exist as a reminder of our frighting and frankly disgusting preoccupation with rape. However, when I was reading reviews of Wings of Honneamise after having seen it, I found myself disagreeing with people’s disgust at this scene. I felt that a lot of people didn’t understand why the scene was in the film at all, and many think the film would be better without the scene. So, I’d like to offer my point of view, what I think the scene’s function is and why I think it is important that it remains.

Right, so, from the outset I am very very surprised how few people mention the scene which comes before ‘that scene’. Some background first: When Lhadatt first comes into contact with Riquinni she is living in a small house outside of the city. Throughout the film we see her life systematically destroyed by the commercialist world they live in; first her electricity is shut off, then her house is demolished to make room for a power plant. She moves into a seemingly unused church after this, which is where ‘the scene’ takes place.

Just before, the two of them meet outside in the rain and rush home together. When they get inside Riquinni takes off her wet boots and some money falls out of them which she shamefully picks up, whilst Lhadatt and Manna (a little girl living with Riquinni) pretend not to notice. For the rest of the evening Lhadatt ignores Riquinni, refusing to look at her until he begins watching her legs from beneath the table. Now, for me, the whole money in the shoe thing was an obvious sign that Riquinni had been prostituting herself to make ends meet. This is reinforced later when Lhadatt mentions that Riquinni ‘must be at…work…’. I’m very surprised that so few people seem to have picked this up.

This fact sort of changes everything. For a start, it goes towards explaining why Lhadatt is so angry with her, and why he allows his frustration to take control. Whether or not Lhadatt is in love with Riquinni is up for interpretation, but it is plainly obvious that he cares for her and that he is attracted to her. The fact that he tries to befriend Manna and offers to give Riquinni the money for a solicitor after her home is destroyed shows that the attraction is not purely physical. So when he learns that she is whoring herself, but still will not consent to anything other than a platonic relationship with him, he is deeply hurt. His anger at her for selling other men the sort of attention that he would have cherished from her sparks his anger and he takes on a certain ‘if they can have you, so should I’ mentality.

But this is not all. Riquinni acts as a pillar of strength for Lhadatt. She renews his pride in his mission, and that what he is doing is right, that he isn’t simply part of what she considers a sinful, unjust world. This is extremely important given that before he goes to visit Riquinni he undergoes a press release in which someone tells him to make up something about why the space program is important and what it symbolises for mankind. By his reaction it’s plainly obvious he is loosing any faith in ‘why’ he’s doing it. Directly after this a news reporter tells him that 30,000 people could be re-homed if the space program cut its funding by half. The reason he goes to Riquinni after this is for some kind of support and reassurance. Instead, he finds out that the purest, most innocent and righteous person he has ever met is prostituting herself. This feels like a betrayal to Lhadatt who is not smart enough to notice the necessity of her actions. He simply feels like she is making a ‘compromise with God’ which is exactly what he suggests earlier when asking why she wont be with him. She replies by saying ‘it’s that sort of compromise that made the world what it is today!’, so it hurts Lhadatt to find her making exactly that sort of compromise. I also wonder, even though it’s never said, that Lhadatt might be able to provide for her if she let him. The main problem of course, is that Riquinni sees no romantic future with Lhadatt whatsoever.

Earlier in the film, Riquinni gave Lhadatt a holy book which he has been reading, trying to understand her point of view. When he finds out she has given into the harsh, sinful side of reality, he looses all will to be anything else and so too gives into his temptation.

During the attack he pauses. As he lies on top of her he suddenly realises what he is doing and stops himself. This moment acts as a symbol as well as a literal event. Lhadatt’s realisation is not just the realisation that he is capable of raping a woman, but that he is part of the military driven society which has forced her into prostitution. It’s only at this moment that he really hears the words of the news reporter. Well over 30,000 people, like Riquinni, cannot afford homes, and are being forced to find ulterior methods of securing income simply to survive because of large scale projects such as the space program. In many ways, the rape of Riquinni has already been carried out, and she had already been defiled by the society they live in, a society which Lhadatt plays a lead role.

None of the above defends Lhadatt’s actions, and in fact shows that he is no better than anyone in the film. He does an awful thing which shocks both the audience and himself. Many reviews I’ve read criticise this scene for destroying a character who had up to this point been rather likeable. I would argue that this is the point of the scene, in which we are shown that nobody, not Lhadatt nor Riquinni are without sin, and are affected by the state of their society.

The later scene, in which Riquinni apologises for hitting Lhadatt backs this up as soon as we realise that Riquinni is not really saying sorry for clocking Lhadatt over the head with a candlestick, but that she is saying sorry for giving into sin. Just as Lhadatt cannot see the necessity of Riquinni’s work, she can not see the righteousness in it. She understands she must do it to provide for herself and Manna, but she sees herself as sinful and wrong. There’s also the possibility that Riquinni is in complete denial about the whole thing. This leads on to something else people have criticised.

Lhadatt doesn’t seem to feel much remorse about the whole thing. It’s never mentioned again, he doesn’t seem to brood over it. In fact, it seems to be almost entirely swept under the carpet. This is generally considered to be bad taste on the part of director and writer Hiroyuki Yamaga, and a sign that the scene served to real purpose other than to shock. I think it’s something else though, I think it’s firstly another example of one of the films main themes; denial (the denial of sin, the denial of being a part of a corrupt government, etc) Lhadatt is denying the event just as much as Riquinni is. It’s also a cold reminder of human nature. I suppose in Lhadatt’s head it is easier to pretend it never happened than to face up to the fact, especially if Riquinni seems content to do so.

These are the films darkest moments, and show our characters in the most negative light. It also comes just in time for the final part of the film in which the action really picks up. Lhadatt is pursued by an assassin in a somewhat rather absurd chase scene, and then we’re onto the final stint in which the rocket is finally launched into space. Then effect it has though, is that we can never really shake the feeling that the scene has left us with. Our connection with Lhadatt has weakened and we cannot wholly root for him any more. This, being the desired effect. Once Lhadatt has reached space, we are left wondering if it was really worth it. If Lhadatt is the kind of man who should be named a hero and an innovator, which is likely to happen, and we wonder if the space program was worth the poverty and conflict that it caused. It’s actually quite hard to feel good for the people of Honneamise.

This is really important given the final prayer of the film.

Just a quick note – I watched the film subtitled, and have realised that it differs a fair bit from the dub. So my understanding of the end is based on the sub translation.

‘Is anybody down there listening to this broadcast? This is mankind’s first astronaut. The human race has just taken its first step into the world of the stars. Like the oceans and the mountains before, space too was once just God’s domain. As it becomes a familiar place for us, it’ll probably end up as bad as everywhere else we’ve meddled. We’ve spoiled the land, We’ve fouled the air. Yet we still seek new places to live, and so now we journey out to space. There’s probably no limit to how far we can spread.

Please. Whoever is listening to me. How you do it doesn’t matter, just please; give some thanks to man’s arrival here.

Please, show us mercy and forgive us. Don’t let the way ahead be one of darkness. As we stumble down the path of our sinful history, let there be always one shining star to show the way.’

This is a great achievement from a flawed species. It could spell new hope, or new disaster. Is it a good thing Lhadatt finally reached space? The answer is simply yes, because it shows that through everything, human perseverance has won through. It is also positive because the men and women of the space program were working towards the betterment of mankind, not a political leg up. However, it is what comes next which would tell. Reaching space may fill many with hope of a bright new era of innovation and perhaps peace, or, as is suggested earlier in the film, if taken into the wrong hands it may spell new and inventive ways for the two nations to bomb each other.

It is neither an optimistic nor pessimistic end to the film, and this is important. I think if the film and the characters had not reached the lows that they had, then the ending would not have been so poignant.

One final note:

I found an article here that describes the scene and says that anyone who defends it is ‘intellectually dishonest or just human filth’. Well, I guess I fall into this bracket, so, human filth it is. But, the writer did include a few things that made me raise my eyebrows:

Apparently, in the commentary track the assistant director, Takami Akai, says that ‘Riquinni reveals herself as a “strong woman” by completely forgiving Shiro and saying that it was her fault’. Well…I don’t really know what to say about that. Obviously I’d argue that it suggests the exact opposite, and that she, like Lhadatt is in fact shown to be very weak. This doesn’t change my analysis of the film, but it does make me wonder just what were the original intentions of the film makers, and if they were consciously aware of all these interpretations people now make.

Another thing that really shocked me was that Akai apparently mentions that he wanted to use animation rcels from the attack as promotion material. Fortunately, people hid all of the production materials from him. Obviously, this can in no way be justified and that all this paints Takami Akai in a very bad light, but I haven’t listened to the whole commentary track myself, so I can’t say anything for sure.

And so there you have my 2 pennies worth! Whatever the film makers intentions may have been, the fact is that ‘that scene’ is not merely one scene among many, but feeds into the whole rest of the film, and I think it has to be viewed this way. To many people seem to take the scene on it’s own, as a horrible and shocking piece, which it is, but when taken as a part of the whole it is not completely gratuitous or unnecessary. Are there other ways the film makers could have portrayed this? Probably. But they chose this way, and instead of just booing it, it’s important to see why it’s there.

Thank you for an interesting take on this controversial scene. As you might expect, the director’s commentary for this film is much longer than just those quotes cited, and in fact Leiqunni, rather than Shiro, is the most discussed character in the commentary. The recent 25th anniversary fanzine on Royal Space Force devotes an article to the moral landscape of the story, as well as the differences between how the scene may be read in the subtitled and dubbed versions.

http://www.magcloud.com/browse/issue/487410

Hi,

Thank you for your comment! Yes of course, in fact I would like to watch the entire commentary myself so that I can make a better assessment of these comments and that bloggers opinion.

This fanzine looks very interesting. I’ll think about investing in it at some point. Did you have a part in its creation?

Sorry for this late reply, if you’re still reading and accepting comments for this blog entry, but I’d like to point out that the blog you linked to by KidFenris features comments by both Carl Horn, the creator of the fanzine you’re asking about, and Neil Nadelman, the english translator for the film. So I think if you want thoughts from people who are considered “experts” on the film, the comments on KidFenris’ blog are invaluable reading.

Now it’s time for me to say sorry for the late reply! Thanks very much for pointing out these comments to me. Great stuff!

Good article!

Never having seen this film before I sat down and watched it this evening. I thought it was really excellent. Of course it’s not a happy happy film and contains many situations that are distressing, not least ‘that scene’. The point of any story is for the characters to develop and, hopefully find some kind of redemption. I think Shiro does this despite his manifest faults and shortcomings. Had he not been flawed there would have been no story.

Yes I agree. I thought it was excellent too.

Very glad you liked it, I thought you would!

You’ll probably be surprised, but I hadn’t even heard of this film. I skipped through your review (trying to avoid the spoilers), but I did get a sense that there is something controversial about it… still, I’ll put it on my to-watch list!

Yes, you defiantly should! This isn’t so much a review as a reflection on one aspect of the film, so I’m afraid it’s rather spoiler heavy.

It’s very good, but please don’t go into it expecting something controversial, as this is not the most important/impressive thing about it. In fact, it seems to me that people’s reaction to the ‘controversy’ sometimes overshadows the artistry of the film itself.

I’d love to know what you think.

Pingback: Sandwiches and cigarettes with Hayao Miyazaki | Sketches, Scratches and Scattered Thoughts

Pingback: Directors In Focus: Hideaki Anno | Pixcelation Entertainment

I just watched this anime, and you are the only one that cleared to me that scene in perfect way, first , the money get from her boots, second, after he refused to eat, she is speaking some religious things that is talking about how truth become lies when they left the lips, and how we see our self’s as good , is not how God see us . Saldy, you are rare example of good watched, great deduction of most importand scene in this anime, I hope to see more reviews from you , specially on Japan media . Arigato .

Dōitashimashite. Thank you for your comment!

I’m glad I was able to clarify some of the meaning of this scene for you.

I’m hoping to do more articles like this, thanks for the encouragement!

The attempted rape scene bothered me so much that I had to pause and google to see what the general reaction was to it, I stumbled upon this, read your reaction and then proceeded to watch the rest of the film. It does still seem to me like a very weird choice to do it but I think it did get me in the right mindset for the final scenes, like you said. So I’m really torn about it.

Yeah I can understand why. It’s a very strong moment for the characters and there’s no going back from it. I’d like to hear your overall thoughts on the film.

Its important to remember that we are shown very clearly what Riquinni does during the day. She works as a day laborer in the fields, gathering wheat. She probably does other odd jobs as well. I am not saying that it is impossible that she is also prostituting herself – that is one possible interpretation, but unsupported by the framing of the movie. However, I think the more reasonable explanation is that she does honest work. If she were really a prostitute, I doubt she would have been portrayed having that look of fear and horror as Shiro is on top of her.

You are spot on about Shiro’s conclusions, upon seeing the money. He resents her apparent hypocrisy, and even rejects the food she offers him, until the bitterness culminates in the dreaded scene. When he sees the horror on her face though, he not only realises what he is doing, but also realises the possibility that he was horribly wrong.

It is a gut-wrenching, but totally necessary scene to understand the humanity of the characters, and the ultimate nature of Riquinni, which is forgiveness. Her ability to forgive him reaffirms that there is someone out there worthy of his efforts to become a space hero. People say she forgave him because she was weak. I think that is 100% wrong. She forgives him because of her faith, and that same faith is grafted onto Shiro as he gives that profound prayer at the end.

It is also unfair to say that Shiro totally forgets about it. Saying to your best friend “Do you ever wonder if you weren’t one of the good guys, but a bad guy?” is a pretty good indication of what was on his mind. Matti’s answer to him of “If you weren’t necessary, you would just dissappear”, followed by a failed assassination attempt, translates to Shiro’s worth not as someone “good” necessarily, but someone who has a very important destiny on his way to becoming someone “good”.

To dismiss “that scene” would be to paint over the dark negative which makes the overall picture so bright.

Hi, thanks for your comment. Yeah, I completely agree with everything that you’ve said!

“To dismiss “that scene” would be to paint over the dark negative which makes the overall picture so bright” This is the reason I wanted to write this reflection, because I felt that too many people were dismissing the film and specifically this scene without any further analysis. The fact you have pointed out that the situation may have been caused by a misinterpretation by Shiro when in fact Riquinni could well be an honest worker shows how many interpretations are possible with this film, and I think this is a film which needs these different views and understandings.

I also totally agree that Shiro doesn’t forget about it and he doesn’t ever forgive himself for it either. In the end he is talking just as much about his own sins as the sins of mankind as a whole.

Wow, it’s been a long time since I wrote this post, I really want to see the film again, thank you for reminding me!

(I know this comment is old, but I can help but say a couple things in light of the current state of affairs for women right now – with the Weinstein debacle still raging…)

You say, “If she were really a prostitute, I doubt she would have been portrayed having that look of fear and horror as Shiro is on top of her.”

I hope you don’t mean that there’s no difference between sex you consented to and sex forced on you? Just because someone is a prostitute, doesn’t mean they want to be raped.

Hi, thanks for the comment!

I wholeheartedly agree with you. No matter a person’s social, professional or psychological situation, assault is assault and should always be seen as such.

This is going a ways back now and I barely remember the film, to be honest. But I recall Riquinni being a loving and spiritual person who is forced into a difficult situation. The fact that the things she chooses (or is forced) to do don’t dilute her kindness and spirituality or imbue her with shame highlights a strength of character. The fact that Shiro sees it differently is a weakness. I believe this is a weakness that we, in our current situation, share and is what has made so many people afraid to speak out until now.

Thank you for this very clear explanation of this scene! When I first saw that scene, my friends and I were completely shocked. Obviously I have seen more graphic and disturbing things in films but that scene was completely unexpected and something I have never seen in a feature animated film. I dismissed the scene as something I couldn’t understand culturally because it was made by Japanese artists. I can see why people would think that the movie would be better without the scene: it’s just casually never acknowledged again, which I think makes it even more disturbing.

That was really interesting.

For what it’s worth you aren’t “intellectually dishonest or just human filth” to me, and I think almost anyone who makes a blanket statement about a subjective opinion on art (or people’s artistic choices) might be a bit nuts.

That said, anyone who listens to country music should be gassed.

(the preceding sentence was not serious.)

It’s almost 2018 now. I watched the movie and felt I should check what others have to say about it.

And I was thinking the same as you. I think the metaphor is that the industrial age wins over the rural world.

At character’s level, well, I think he needed that moment to realize who he is and who we are, to take that in space with him, and pray for us and for himself. So it is a moment that completes a somehow ignorant and superficial man, making him a more profound sinful one.

Thanks for writing!

Thanks for reviving such an old post! haha

I think you’re right about the industrial age winning over the rural, however, perhaps Shiro’s self-reflection at the end means there is still hope to build a world that honours both…

You’re right. Perhaps seeing his sin is a way for him to truly start on the path of becoming a better man.